Phytoremediation is such a natural process, you could almost say that it has been around as long as the Earth itself has. However, the intentional use of big fields of certain types of plants for the purpose of cleaning up the environment, began in the 1990s (Dowling; Macek, 2006). Phytoremediation developed from bioremediation, the use of bacteria to decay all of the organic waste in our soil. The use of bioremediation was popular for thirty years before scientists thought to use plants instead. This thought came from Dr. Ilya Raskin, a Russian-born scientist, who, after coming to the United States and working with a company called Envirogen Inc., and their use of bioremediation, wanted to find a better way to clean up the environment (Arnold; Hazuka; Herring; Murray; Williamson, N/A).

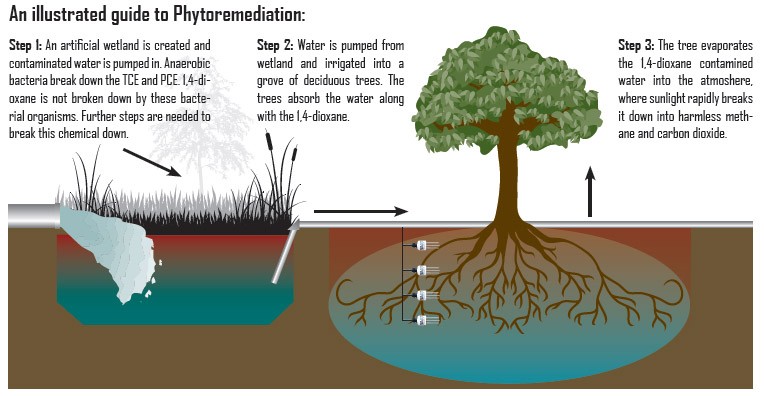

Phytoremediation works in a much simpler manor than most biotechnologies. Why? Because Phytoremediation is a scientist's utilization of life's natural processes. How exactly does it work? When some part of the environment - say, water - is polluted, a bunch of scientists go out and plant some plants. These plants take in the polluted water, then evaporate the water, retaining the pollutants, so that the water is released back into the wild and the pollutants can be removed from the environment.

The one problem with phytoremediation is that all good things - especially nature - take time. And the use of plants to clean up pollution? That takes a lot of time. During one study in Oregon, where hybrid poplar trees were planted in an abandoned lot of roughly four acres in an industrial/commercial part of Clackamas, the growing trees were found to have absorbed some of the pollutants, mostly within their trunks. However, after four years, the soil and water appeared not to have changed (US EPA, 2011). The pollutants in the trees proved that phytoremediation was indeed doing its job. But how long would it take before it was done?

The answer is not particularly known. However, scientists are working on another branch of biotechnology - genetic engineering - to manufacture plants that will be able to perform the processes of phytoremediation much more quickly - which will result in less pollution in less time (Moffat, 1995). An example of this are Arabidopsis thaliana plants, which have been genetically modified to express two genes (mercuric reductase, or merA; and organomercurial lyase, or merB) that help in the removal of toxic methylmercury from wetlands (BioInfoBank, 2000).